This is the text of a talk given by Alex at the Technical University of Dresden in Summer 2019, covering the political economy of computational propaganda, the emergent properties of digital communications networks, the possibility of predicting and tracking social change in the 21st century, and the contemporary crisis of subjectivity and citizenship.

A talk on Politics and Change in the 21st Century. Many thanks to our friends at the Technical University of Dresden for the invitation to speak on this subject. I only hope it didn’t make you too pessimistic!

Thank you for having me. I’m going to assume that if you haven’t found our website yet and read into some of the projects I’ve worked on over the last couple of years, then you can soon. Given that, I wasn’t intending to go into technical detail today – however I’d be more than happy to talk more about such things later.

Instead, I was hoping to use this as an early attempt at an essay to cover the emerging phenomena I think we have witnessed during the course of the last few years, as well as our own attempts to give a narrative as to why they take the shape they do.

As promised, I’ll try to contextualise this as part of an analysis of political economy – however, where once I would have been happy to add “Of Computational Propaganda/Manipulation” I am no longer sure that it is appropriate to assume what that project held at its outset was the normative model of culture, media and power.

I should be presenting a paper in Brisbane next month where we’ll talk about our findings under the title “An Audit of the Political Economy of Computational Manipulation”. If anybody came here hoping to hear that, get in touch with me and I’ll send you a copy.

My colleagues at both Oxford and Etic Lab have been quite rigorous in their attempts to quantify and analyse the dark art of the algorithm and in particular the effects of the burgeoning social industry on electoral systems. In particular, I really recommend the “Data Memos” the Comprop team publish around electoral events and the Junk News Typology they have maintained since 2016.

I don’t doubt the value of watching these phenomena emerging, nor in accounting for their disappearance. I sympathise, if not out of agreement that it is what has happened, with the desire to remove the spanner from the works of our political and cultural life that bad actors have placed there.

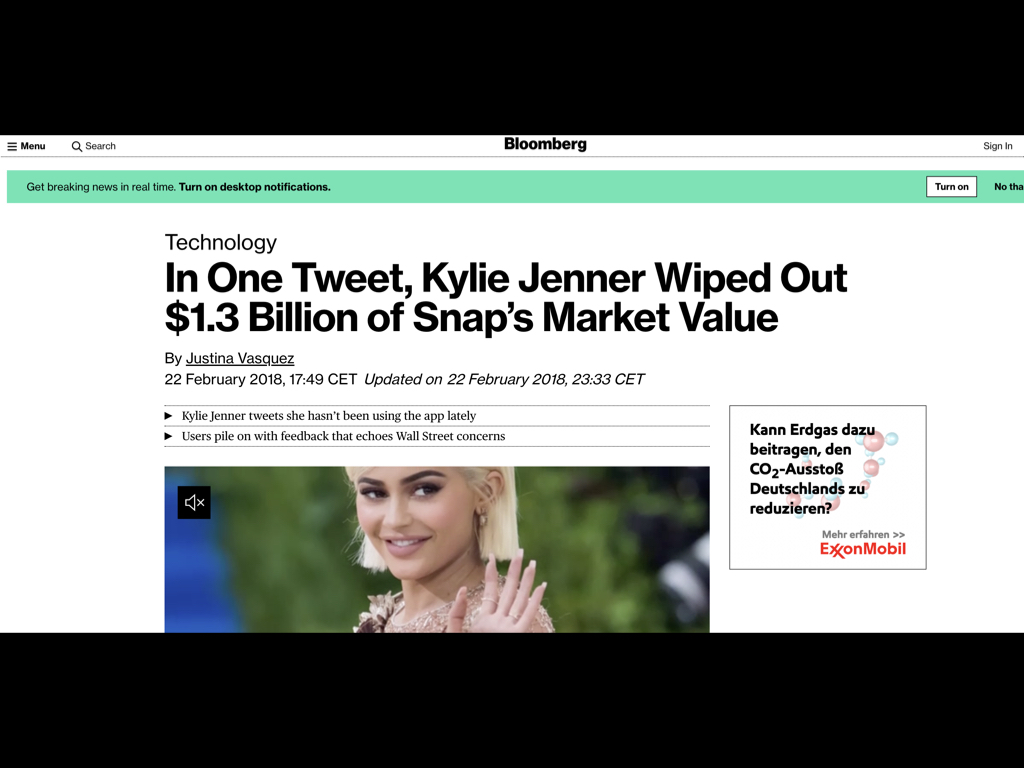

But the more we have been involved in watching, developing and interrupting communities across the digital landscape, the less that story has enough descriptive power for me. The economy of digital writing, in which a single tweet by Kylie Jenner could wipe $1.3 billion off the stock value of Snapchat, has shattered the economies of scale by which we organise information and take meaning from it.

We are invited to create new identities for ourselves; competitively, imperatively, exhaustingly. We see effort made, and rewarded, that could never be thought possible. It looks to me like we are labouring on the birth pangs of a new nation and there is a lot more work to do to audit that.

Dark Patterns

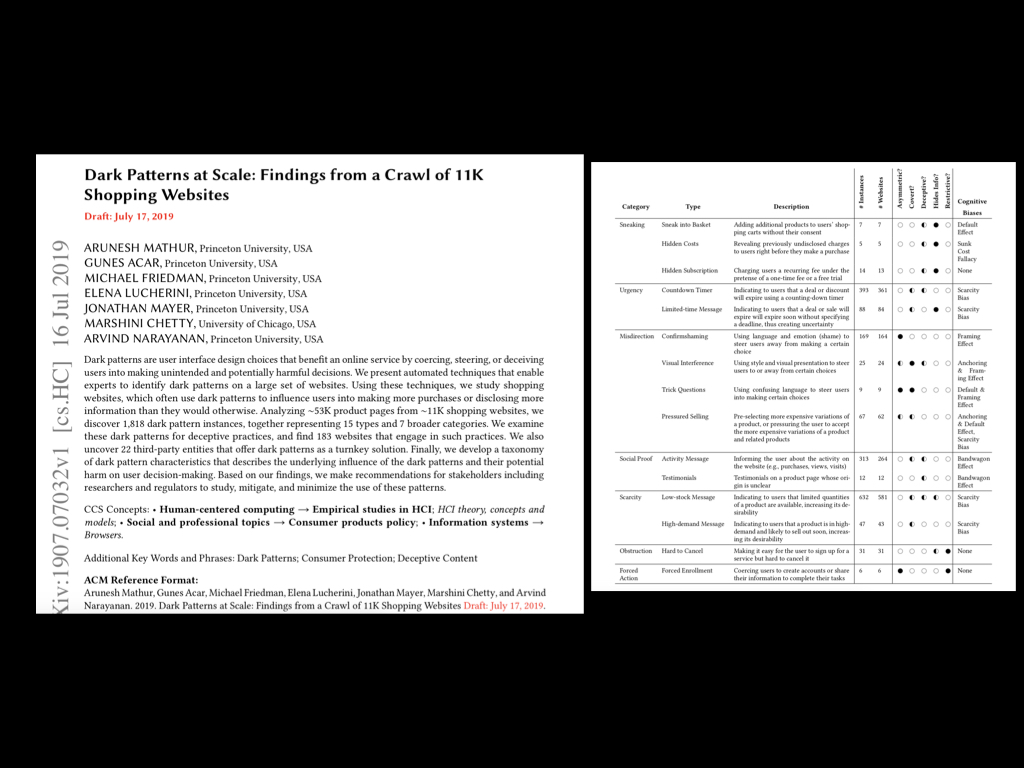

Earlier this year a team of researchers from Princeton and Chicago published this draft paper on the extent to which “dark patterns” were deployed on the internet’s most popular websites.

Dark Patterns were defined as interface design choices that benefit an online service by coercing, steering or deceiving users into making decisions that, if fully unformed and capable of selecting alternatives, they might not make.

I highly recommend reading the paper, including their earlier work on defining the taxonomies of dark patterns. In this paper they report as their main findings:

- They discovered 1,818 instances of dark patterns on shopping websites, which together represent 15 types of dark patterns and 7 broad categories.

- These 1,818 dark patterns were present on 1,254 of the ∼11K shopping websites (a lower bound of ∼11.1%) in the data set. Shopping websites that were more popular, according to Alexa rankings, were more likely to feature dark patterns.

- In using their taxonomy to classify the dark patterns in the data set, they discovered that the majority are covert, deceptive, and information hiding in nature. Further, many patterns exploit cognitive biases like the default and framing effect. These characteristics and biases collectively describe the consumer psychology underpinnings of the dark patterns they identified.

- They uncovered 234 instances of dark patterns—across 183 websites—that exhibit deceptive behaviour.

I don’t think I am anywhere near the first person to have suggested to you that the internet looks like a giant tool set for this kind of work. I have seen explicitly and at great expense the people doing this using expertise from semiotics, sociology, behavioural psychology, anthropology to refine their methods.

For example, I have personally worked with charities on severely limited budgets doing A/B testing, rapid prototyping to recruit donors, volunteers and test the effects of their content on their audience and I recently came across Troll-based testing for political campaigns where you release something to the trolls, gauge their reactions and adapt accordingly.

This work is rigorous, done at scale, all day every day across every continent and, as the psychologists I work with have pointed out to me, this kind of experiment in in-flight adjustments for manipulating humans has never been done before, despite the dreams of their 20th century colleagues. You can conduct an experiment on a scale that has simply never existed before, ever. You can do it, refine your method and roll it out across a continent in an afternoon.

In fact, the mathematics of behavioural conditioning are so well understood and so comprehensively deployed that it is impossible for any given individual to really understand what influences they might be subjected to at a given moment.

So, a personal anecdote now. I know somebody who works inside Facebook who’s colleague recently ‘Fessed up to mistake he had made in which 38 million people lost access to the platform. Obviously worried for his career he reported it to his boss who responded something along the lines of – Don’t worry. In fact, why are you even bothering me with this? There are 1.3 billion live users of Facebook so that number is just a drop in the ocean.

What I want to spend a minute on though, is the implications of the emergent “next level” of this system.

A few years ago we started to work for commercial clients looking at the implications of Artificial Intelligence. I have come to the conclusion now that those arguing about the ethics of AI have missed the point so completely as to need shaking awake. You don’t need an AI to manipulate people. That’s what this all is. And the emergent properties of the network are under nobody’s control.

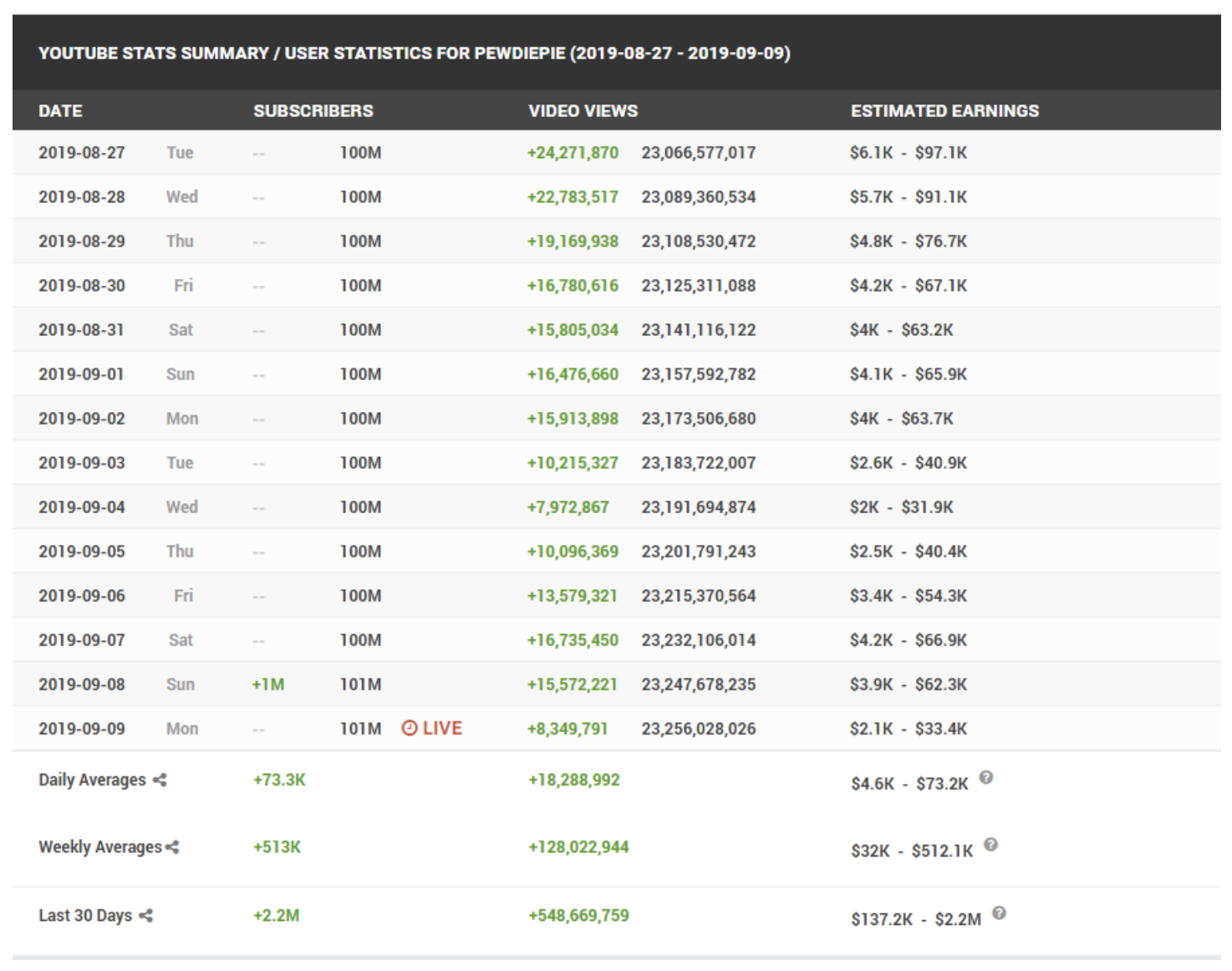

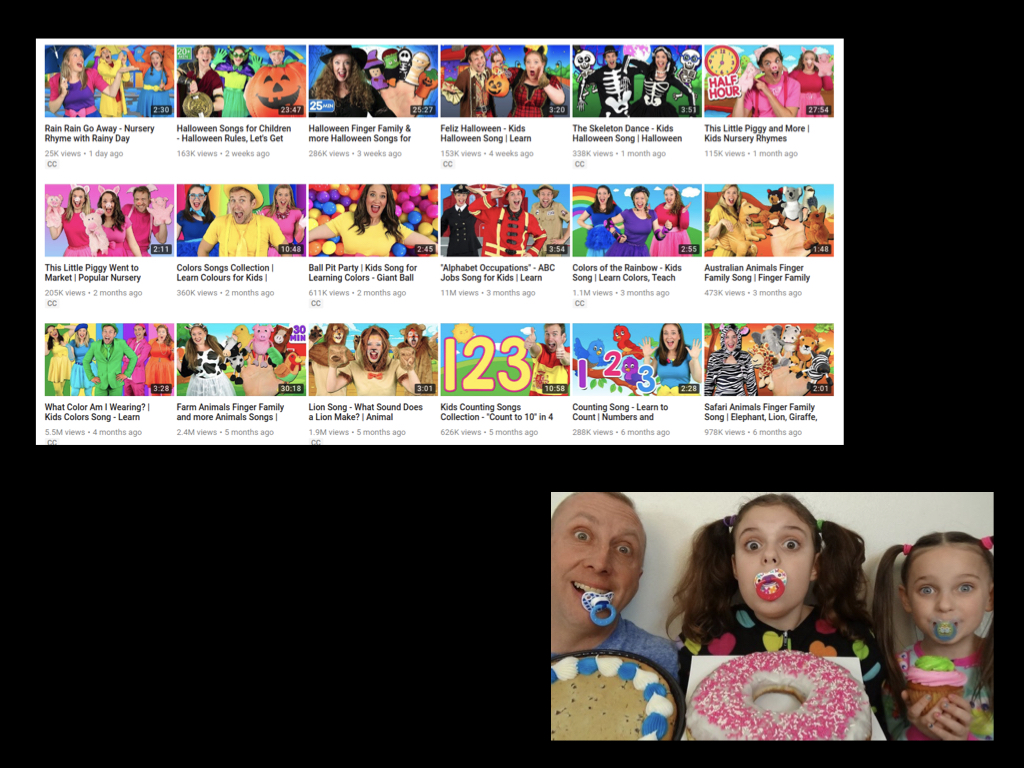

I would argue today that one of the biggest political events in modern North America was the Monetising of Youtube pages – in terms of the breadth and scale of its impact.

If anyone has counted, I would estimate that more professional politicians have emerged out of Youtube than any domestic legislation. Anti-Vaxxing as a political community has produced books, conferences, training courses and donation buttons. How-to guides on become a Youtube millionaire through, for example, right-wing content, are all over the net.

In terms of both political economy – money being made and spent on monetised Social Media platforms – and of cultural capital spent and earned, I cannot think of anything comparable to have had such an effect in the same amount of time.

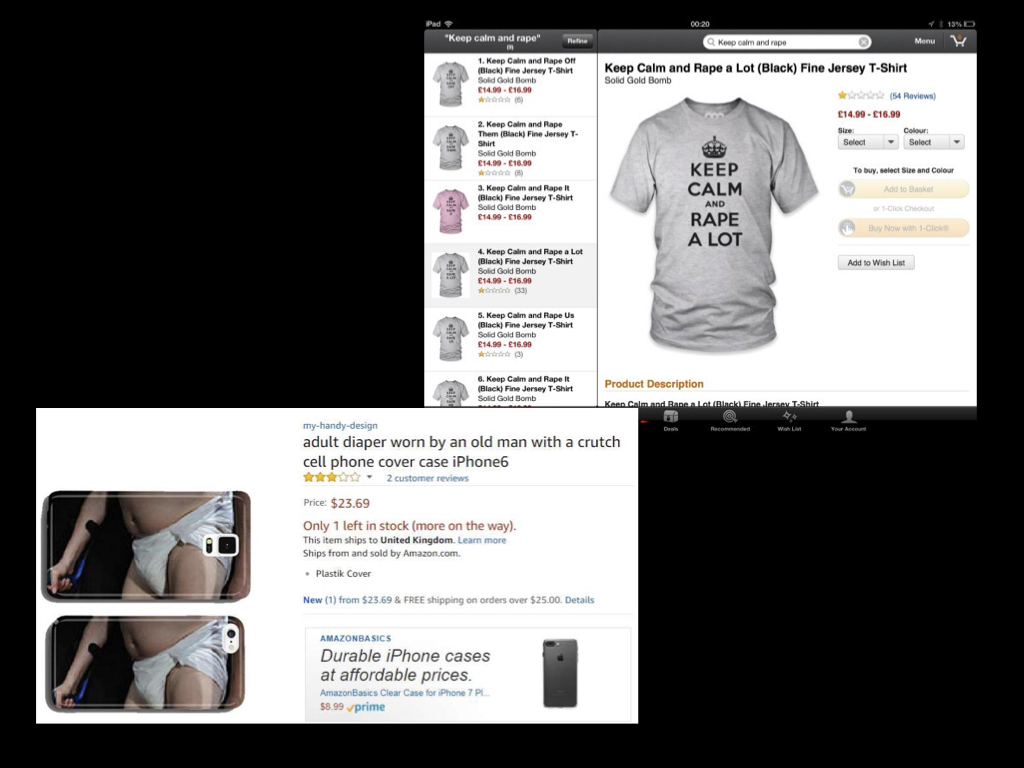

The idea that there are persistent, consistent and ubiquitous attempts to manipulate us all in order to create experimental data that can be used to further manipulate people for commercial ends going on right across the net every day is bad enough. But thats a level on which we can choose to understand it if we put a lot of effort in. I think there is a degree to which most of us who are looking can point to the Skinner Boxes we find on Amazon and say we can understand why and how that is happening and what we would do if we could collectively agree it was wrong or a bad thing to be doing to each other.

I’m not so sure we can say the same of the emergent phenomena of the machine, such as the strategies for a career path being shared by millionaire bigots, to single (or even no) issue parties entering government.

Reinforcing people being a political arsehole by giving people fame and money is a bad plan. But the difficult point is that its nobody’s plan.

Predicting the Future

It is not possible to predict the future but it has long been recognised that it is eminently possible to extrapolate from the past with a good deal of success, under the right circumstances. The reasoning behind this essay is that this particular approach is very much under threat as a result of the rate and scale of change around the globe.

Essentially, corporate culture and political culture are not able, for structural and idealogical reasons to either anticipate change or indeed drive it as they might once have been expected to do.

To illustrate this, Donald Trump is finding it almost impossible to get the help of car makers in winding back the car emissions standards from the levels set by the previous administration. A paradoxical state of affairs given the behaviour of the car makers over the last 100 years. Energy providers are adamant that more expensive cars (they say) with higher emission standards and better fuel economy are bad for the consumers and business. It’s not true and its definitely not acceptable, even in the USA.

The car makers have to deal with a plurality of actors, in this case the Federal Government and the State of California, something they do not like and for now they are adamant they cannot serve two masters. Moreover the old form of capitalism is not the one they can back, the prospect of years of litigation and multiple standards for something as large scale as car production is just not on.

Given that a car made for California (and seven other states that follow Californian standards) will meet Federal standards but not vice versa they are voting with their feet and against Trump. Ironic but inevitable is the discovery that cars meeting the higher standards are cheaper for the state and manufacturers but also consumers not least due to fuel costs.

Here is a worked example of the current situation, industrial giants, once partners in driving the state to serve their best interests are now at odds with one another. The state is at odds with itself the absence of a political consensus causing structural problems on a very large scale. Finally we have the consumer publics, large numbers of motivated citizens with profoundly differing views: those for whom reducing emissions from cars is common sense and an urgent priority and an other very large group that sees this development as unnecessary, coercive and expensive.

For now trends and issues that are relatively new such as whole-life costs, the systemic role and position of the product and producers and a breakdown in existing alliances all contribute to the chaos.

A state divided against itself (California versus the Federal Government), an industry that is no longer hegemonic (car manufacturers in the US) and another that is huge and commands great power (energy companies) but whose time in the sun is rapidly drawing to a close – however hard they may fight, they are and will need to continue to fight in order to preserve their position.

(Since I wrote this there have been some developments – Trump announced a Justice Department investigation into rogue manufacturers who are resisting his roll-back of emissions-requirements and fuel consumption targets. Then congressional Democrats announced an investigation into the investigation. Trump has announced he intends to remove California’s ability to set its own targets, which the State government intends to fight in court. Such incoherence may not be visible in all countries, but no one country should assume it is immune.)

All of these factors expose what once could have been taken for granted and was always hiding in plain sight – the natural order of things. The interlocking systems of power, influence, production and profit that have sustained for so long are now increasing in visibility if not significance, as they waste away before us. Systems are becoming visible due to their failure and the new order is by no means clear, not even on the horizon wherever that might be. The natural order or Hegemony is breaking down and taking predictability with it.

So what does this have to do with anticipating change? My thesis is simple, the dissolution of the the hegemonic status of productive capitalism of the 20th century is in turn driving and being driven by a crisis in the social order.

So what capitalism and market economy states wanted and promoted was; independent and personally responsible, socially isolated, autonomous, decontextualised, a-historical subjects.

This parallels this conception of the citizen. Latterly known as citizens and once as customers and now consumers, they will enjoy a different relationship with a different form of statism.

I am predicting that, in part at least, that subjectivity created by and an enabler of 20th century capitalism, will became an engine for change as it morphs into something else again.

A new subjectivity is being brought into being and with it social practices and movements that will change what it is that is taken to constitute civil life. In the meantime corporate actors will be permanently surprised to find themselves suffering from, helping and indeed making some of these changes happen as well as running along trying to keep up with them.

The evolution and reduction in the role(s) and responsibilities of the state will be one of the great engines of economic development in the 21st century. Not just because it drives the success of the companies that take up the mantle of providing the once public services as the state shrinks. But rather because the new state will require new forms of public practice and behaviour as different trends evolve.

The citizen narrative will evolve as collective responsibilities develop and socially connected and mutually dependant groups embedded in a locality that is significant to them and the way they live their lives interact with commerce.

Companies will also have to recognise and develop a wider role and vastly different responsibilities than those envisaged by corporations in the 20th century. All of this will take years to come about and at the heart of this process will be the need to respond to climate change, a rapidly evolving global economic order, the impact of technology, the creation of new political practices to reflect the new complexity, combined with a need to reflect new constituencies, their aspirations and requirements.

For now at least – as we can see with the rise of populism, demands for democracy and climate activism – the public(s) will be wrestling with the same challenge as commerce – the seeming chaos of near perpetual change.

But change is coming and on a scale that has rarely been encountered in history without war and pestilence. The one enduring human quality that will influence how this plays out is the all-to psychological requirement that change should happen elsewhere, to someone else for preference and should be over quickly because we see it as an unpleasant event and not a process. Unfortunately this time none of these requirements will be met, for any of us.

Evolving subjectivities – who am I, who are we?

Here I have taken the simple step of arguing from the converse of those tendencies described above but which are present to a degree in all of the financialised economies and to a different extent across the world.

Perhaps the first change in the evolution of the subjectivity I wrote of above is the rise of the idea of co-dependancy, recognising and acting as though it were true that we, human beings, citizens, parents, children etc. depend upon others for our material existence and happiness.

If this tendency does expand it will change a good deal about the way some us see the world and – more importantly – how many of us might choose to act within it.

It is perhaps easy to argue that many cultures never made the mistake of ‘forgetting’ this truth in the way that colonialist and technocratic societies have. But we can see how many events and trends in the global community might drive this sensibility to the fore even where it is precisely the opposite what has been held to be true for so long.

Following on from this is an emerging sense of collective responsibility, that nations, cities, companies, professions, regions, villages should call for and express the value of collective thought and action. More precisely it is in the idea that people in all of these different communities of interest should and will want to express the idea of shared responsibility in the form of communities of practice – do things about the world because they own the problems that are to be confronted.

We all look at the world and see different things. To take just the example of YouTube I think it is clear we now have tools at our disposable for radically reconfirming and solidifying those differences by introducing us to others who share them and then match us with more and more of what we want.

The communities that we have watched emerging on YouTube provide us with a good picture of what it is they need. A strong hierarchy based around family, empathy with animals, the need to feel good about yourself or be good to yourself, attention from others for your thoughts, hopes and dreams – these are needs that are really complex and can be expressed through those sort of activities.

Both in the sense that they’re vulnerable to the ways they come across information but also in that they have real needs that aren’t satisfied by or present in other forms of behaviour these people are doing real cultural work – making sense of the world.

It’s work that needs to be done by all people and what we are finding is that, in the affordance structure of the internet such that people can do that for themselves and amongst non-hegemonic cultures. This is a cognitive economy where the labour of being themselves is not labour and to each of us that is so valuable.

When we looked at how right wingers were using reddit and 4chan to organise in 2016 we watched them ask questions, look for support and developed common practice. A place where they didn’t have to explain themselves.

Amongst anti-vaxxers on social media what we find is that they’re commonly looking for confirmation of their world-view without having enough information. A frequent question, especially with an ill child is “Have I done the right thing?” and the unfortunate situation is that it is very easy to find someone who will reply “of course”.

Here we can see the impacts upon politics and commerce as this sense of what it is to be a person and how to behave flies in the face of the constructed personhood so prevalent in industrial and post industrial economies.

To put matters crudely, a populace taught to express its values by voting at irregular intervals for a complex platform of ideas and actions and consequently to look to the state at every level of society to identify legitimate problems and solutions, is no longer served by this approach or the political process it embodies.

No doubt politics will endure but what and how it goes about its business is changing dramatically and we have a long way further to go. These ideas feed into the storm caused by the rapid evolution of the next idea, recognising that we are or should be socially connected, that we cannot be treated as and do not seek to exist as though it were true that our social connections are irrelevant or simply do not exist.

This is important because the state has to recognise the idea of community for example, but does not recognise its ubiquity or form. Insofar as there are ‘legitimate’ communities which the state can ‘see’ and deal with they are forced to accept the role of many different intermediaries and structures designed to limit their power or salience in society.

This is because the law, healthcare, policing, social care etc. does not recognise poverty, ethnicity, gender, family and etc. as it acts to influence if not determine our social existence. Of course these institutions often have to work in terms of these ideas to understand what we can all see, but true power used to lie in denying the legitimacy of such concerns when the state or its agents actually act.

The current situation where multiple digital platforms exist which are capable of bringing new communities of interest and practice into existence, sustaining and expanding them and indeed to give them material form is a huge problem for the neoliberal state and the subjectivity described above.

Not least because of the technical affordances of the digital forum; denying the old logic that talking to the public, any public, required capital resources, took time to deliver material, material that was written and delivered in a usually top-down fashion, created and delivered at scale, passive consumers for ideas and information and content that could be policed. All of these truths are long gone.

The key point here is that the population are not consumers anymore but users. This is precisely the sort of change in the subjectivity, the sense of personhood, that is happening right now and for which existing ideas and institutions are so ill-prepared.

So much so that the attempts to manage, prevent, monitor, explain and militate against mass public discourse, (such as campaigns against fake news) appear ludicrous to many and utterly indefensible to some.

To the extent that a reaction to the existence of these digital spaces and the opportunities for bigotry they afford is to contest at every opportunity, every single transaction in which somebody is racist or sexist then they are creating a very undesirable place to be. No-one wants to be challenged to their core in a conversation and I remain deeply skeptical of any attempt to fact-check or police those communities through digital interactions.

The idea that someone, preferably the state or at the very least organised capital has the right and responsibility to manage our social discourse is full of ambiguities and paradox. It is fascinating to watch nation states, academics (including myself) and the press struggle with what they perceive to be the self-evident need to police public discourse and the fight to maintain the requirement that other states – say China, to do no such thing.

But this is to ignore the more important fact which is to say that the existence of an arena in which public speech is not local and managed but denies the constraints of time and place is a huge problem for neoliberal political economies. This cat cannot be put back in the bag. By which I mean that people who are part of such processes no longer see their role in political discourse and the outcomes in the way they once did. Politics must change because Mr Zuckerberg cannot be tasked with winding back this clock, although no doubt we haven’t seen the last of the efforts to make him try.

This shock for the political economy is two-fold; one is caused by the prospect of ‘bad-actors’ interfering in the political process and the other is the recognition that huge swathes of the public can themselves readily become ‘bad- actors’ if the terms of engagement with political discourse are not properly managed.

Merchandise

The content agnosticism of computational capitalism has political valances, but the algorithm’s effects go well beyond political content. Perhaps you’re familiar with the writing of James Bridle from about a year or so ago where he exposed the extent to which children’s content on YouTube was being algorithmically generated – (and by one account sometimes to the extent of real-world actors being hired to act out a generated script) – with erotic or violent themes created to meet a demand identified by algorithm?

Similar stories abound from the last couple of decades. Ghosts in the machine which generate weird or terrible content, from videos to merchandise available on Amazon designed from the aggregated wants of the machine.

In other words, to reflect what had been learned from watching users: clicks, searches, watch times. Software herds users together into temporary tribes based on data. It establishes correlations over whole populations between certain types of content and certain behaviours: stimulus and response. It works only because of response. There has to be something in some viewers, waiting to be switched on.

Platforms thus divine our desires as we confess them, listening intently as our collective wants surface to be manipulated, engineered and connected to a solution.

And as author Richard Seymour has written: “New technologies have only been as successful as they have been by positioning themselves as magical solutions. Not just to individual dilemmas, but to the bigger crises and dysfunctions of our world. If mass-media is a one way monopoly on information, turn to the feed. If the news fails, turn to citizen journalism. If you’re underemployed, bid for jobs on TaskRabbit. If you need money and own a car, use it to make some more on the side. If you’re undervalued in life, bid for a share of micro-celebrity on Youtube. The business model of the platforms presupposes not just the average share of individual misery, but a society reliably in crisis.”

Conclusion

Not only do algorithms, platforms and our hardware invite businesses and other actors to manipulate the public, they provide the tools whereby we can do that to one another. Not only that but the political economy is exposed to disruption at scale because we are monetising the act of doing so.

Phenomena such as the far right celebrity are emergent properties of a system whose dimensions include, but are not limited to technology and the digital world, but is actually much more complex than Twitter provided easy access to 280 characters in which to be rude to someone.

Just because much of what we see happening is unintentional, doesn’t mean we can afford not to understand it. Similarly, any attempt to understand – and worse yet, control – what is going on through the lens of conventional politics will probably only serve to increase the rate and volume of chaos.

Whatever we are, whatever we are becoming – collectively responsible, socially connected, dependent upon others, with a history and a context whether it be from place, sexuality, race, or social class – people will need to be seen and perhaps want to be part of something; from the past, in the present and looking towards the future. If we are to meet it, we must do much, much more than audit and refine our technical skills.