Video and documentation of the webinar briefing on our Report, a feasibility study into the application of big data and AI in the access to justice sector, which took place on Tuesday 2nd June 2020.

Covid-19

In light of COVID-19, our findings and discussion about sector digitalisation and the dangers of digital desertification have become more urgent. We discussed our suggestions for future initiatives on the basis of what we predict the new world order will require of the sector and what it may afford.

Webinar Slides and Script: Introductions

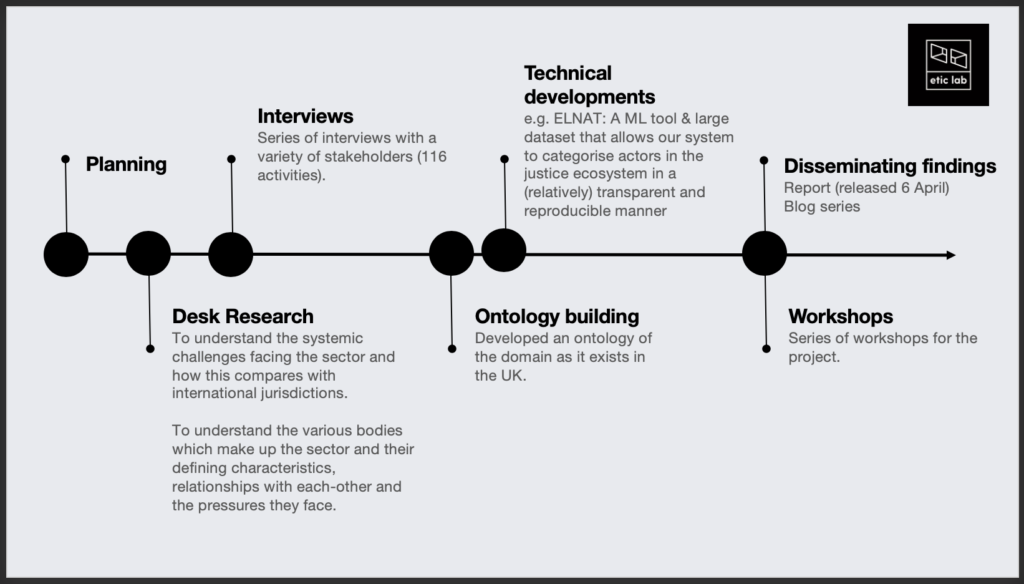

The plan for today will be to spend the first section focusing on the project itself, we’ll then briefly touch on our methodology.

We’ll then finish with describing the pros and cons of the technological candidates put forward and taking questions.

Throughout we’ll be talking about how we can apply some of our research to the COVID-19 context and we invite you to help shape what our next steps will be.

Emily MacLoud (EM): My name is Emily. Throughout this project I’ve contributed by undertaking some of the fieldwork activities we’ll describe later on. I’ve been working within the access to justice sector for a number of years and value the insights that have been generated as a consequence of this project… I’ll now pass it over to Steph so that she can introduce herself…

Stephanie Moran (SM): I’m Stephanie Moran, I’m an Associate Partner at Etic Lab. I have a background in the cultural sector, in art and libraries, and am doing a PhD in transdisciplinary tech Research. I have done a little of the fieldwork on this project, but my main contribution has been in analysing the results with the rest of the team, and working on building an ontology of the affordable justice sector – something I’ll be talking about later when we discuss methodologies.

EM: Thanks Steph. I also want to briefly introduce Tom [Barrington], Kevin [Hogan], Richard [Woodall] and Alex [Hogan] – the other team members who will be available to answer questions at the end.

Etic Lab is a digital research and design consultancy based in Mid-Wales.

As the name suggests the Lab tries to analyse cultural phenomena from an outsider’s perspective… Ultimately, the Lab tries to reduce uncertainty about what to do next.

If you’re interested in the work of Etic Lab – we encourage you to reach out to one of the partners about other work they’ve done.

We’re trying to balance these two approaches:

- We take on an ethnographic approach and

- also an alien perspective…

We have a duality of perspectives….

The project is an attempt to address the challenges and opportunities within the access to justice sector. Funded by Innovate UK and Etic Lab, the project is being carried out in partnership with various actors from within the sector, including LawWorks, RCJ Advice, Support Through Court and the LIPSS.

… In setting the scope of this project – we took our working definition from soft systems methodology (which Steph will talk about later) – which argues that human systems do not simply consist of inputs, processes and outputs but are also affected by the interests and worldviews of all the actors involved in it. We also benefited from building our ontology after the fieldwork was complete. As the report highlights, this process had a bi-directional impact – meaning that the process of defining what we were studying helped us to refine the limits of our work and also pushed us further towards understanding what interventions were feasible.

The study aims to systematically identify the difficulties involved in applying technological solutions to the sector, and then propose a range of technological and organisational strategies which address these fundamental issues.

This study was a feasibility study – that is, it was designed to evaluate the possibility of applying AI, data analytics and other contemporary information technologies to support and enhance the sector….

These two questions guided our work:

- How they would need to be implemented?

- Which specific technologies might serve this goal?

To address this we studied the system as a whole. We didn’t want to stick another plaster over a systemic issue.

It goes without saying that since COVID, this system has changed drastically.

Not only have shop fronts closed, fundraising events have been cancelled and normal service delivery channels have been directly impacted and this has had trickle down effects into every facet of service delivery. We have seen the mass adoption of new ways of working and adaptability on a scale never seen before.

This style of implementation was definitely not what we had in mind when writing the paper. What we do note though is that this presents an opportunity for a multi-phase implementation/response programme, starting with immediate firefighting and the adoption of a range of energetic and resourceful local efforts to address emerging problems, and progressively shifting to questions of how to keep providing sustainable services. Notwithstanding the importance of social and organisational transformation which is needed, most of the technologies that are proposed in this report have applicability.

In reviewing systemic impact we wanted to highlight was we did not focus on:

We did not focus on generating a set of guidelines for digital innovation or adoption.

Neither were we interested in developing standalone digital applications.

Instead we were interested in exploring the interconnecting and interdependent issues, making up the whole ecosystem, and proposing interventions (which would necessarily involve strategic and organisational development).

Over the course of the last year a number of key reports have been issued by colleagues in the sector which were extremely valuable and we thank the authors as we were able to stand on their shoulders so to say.

With this in mind we had one key finding, which personally, was the most striking:

The concept I am referring to is aridification.

I’m going to read direct from the report (p 43):

The term aridification describes the sequences of events – changes in the weather, soil, flora and fauna, the effects of human activities – through which once a healthy ecosystem dries out. This state can only be reversed through a series of coordinated systemic interventions which go far beyond the scope of water management – planning vegetation, reintroducing wildlife, geo-engineering and moderating human activity such that underlying cycles can be regenerated.

Digital Technologies in the Access to Justice Sector: a Strategic Overview

I do love an analogy and I think this sums up what we have seen. The sector has spent nearly a decade of adapting to the new aridity. It’s time for planning, engineering and moderating.

SM: And important to note that the results of acidification are not reversed simply by putting the money back in – the ecosystem has irrevocably changed and cannot be restored exactly as it was.

We developed our methodology with this in mind, and with a view to scalability, sustainability, and avoiding pilotitis – the endemic problem of a proliferation of technological solutions which don’t get past the pilot stage because they are not scalable or not sustainable, for example due to lack of capacity for sector-wide adoption or investment – Emily will speak later about our criteria for this.

We believe the most successful solutions come from a well-defined problem. We set out to clearly define what our problem consisted of before launching in.

In order to identify the points in the system at which an intervention could have the most impact, we needed to understand the space it is operating in: who the different actors in the system are, what their goals are (which may not all be the same), how much collaboration and systemic overview there is, and what they want.

We chose to use techniques from a method called Soft Systems Methodology – a road-tested method for analysing complex social structures by building conceptual models which describe the problematical situation from a variety of different perspectives.

We were coming to the sector with fresh eyes, from the outside, guided by our partners.

In order to gather the multiple perspectives we needed, we did reams of reading, of academic and industry papers, nationally and internationally to understand sector challenges and relationships, and how it compares with international jurisdictions – you can find our full bibliography at the end of the report – essential resource for further research in the field.

We also carried out fieldwork, travelling the length and breadth of the country to listen to staff at all levels, from frontline to CEOs, to gain multiple perspectives, to have real cases to base our analysis on, and build up a whole system overview. interviews were designed by Etic Lab’s Dr Kevin Hogan, an organisational psychologist with decades of experience in designing and carrying out qualitative research.

They were organised around a set of general questions, themes and prompts with the aim of balancing our wish to allow the interviewee freedom to lead the discussion – which leads to unexpected insights, things we would not have thought to ask about; and our need to gather specific forms of information.

I certainly found my assumptions contradicted on several occasions, as did the rest of the team.

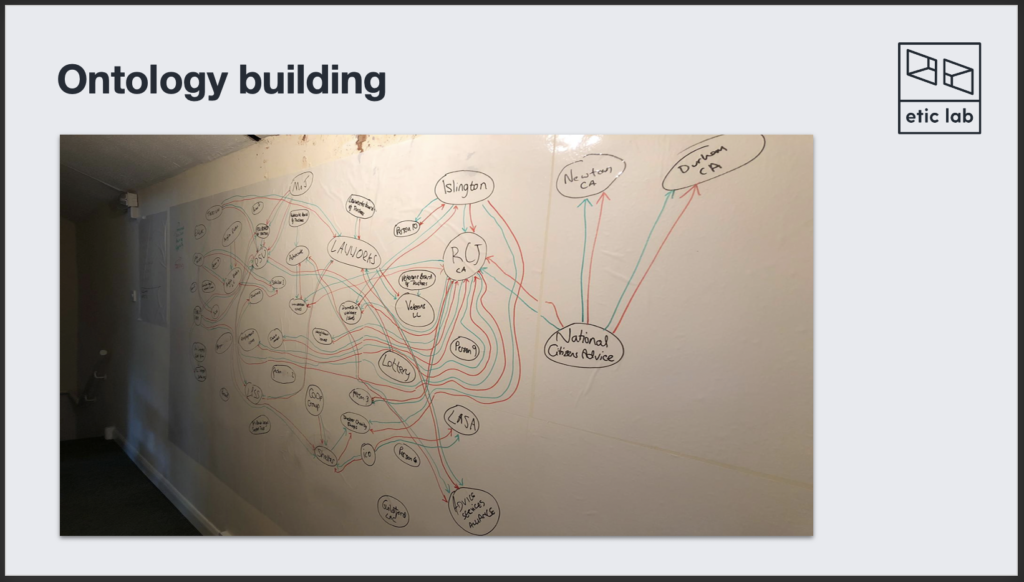

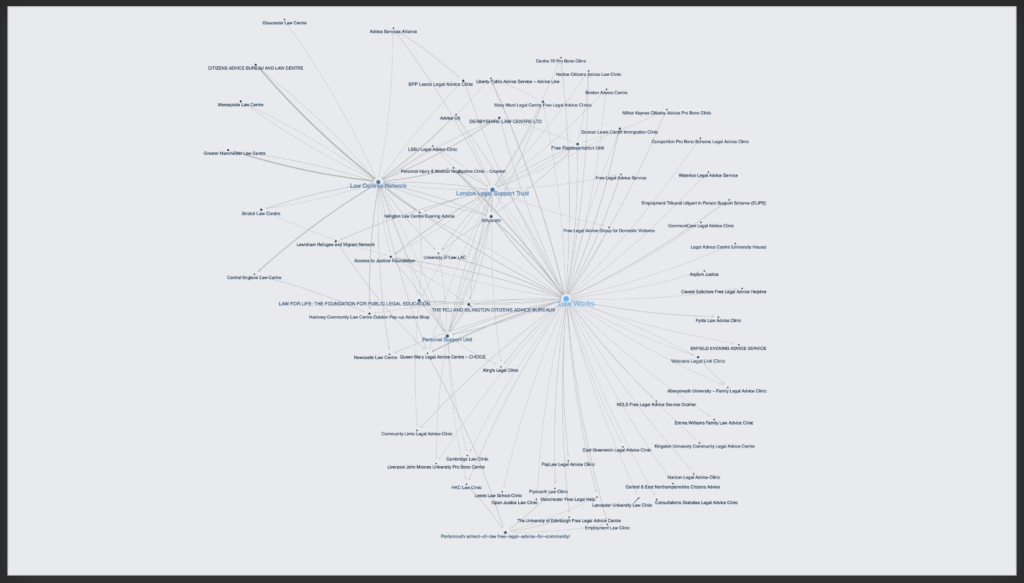

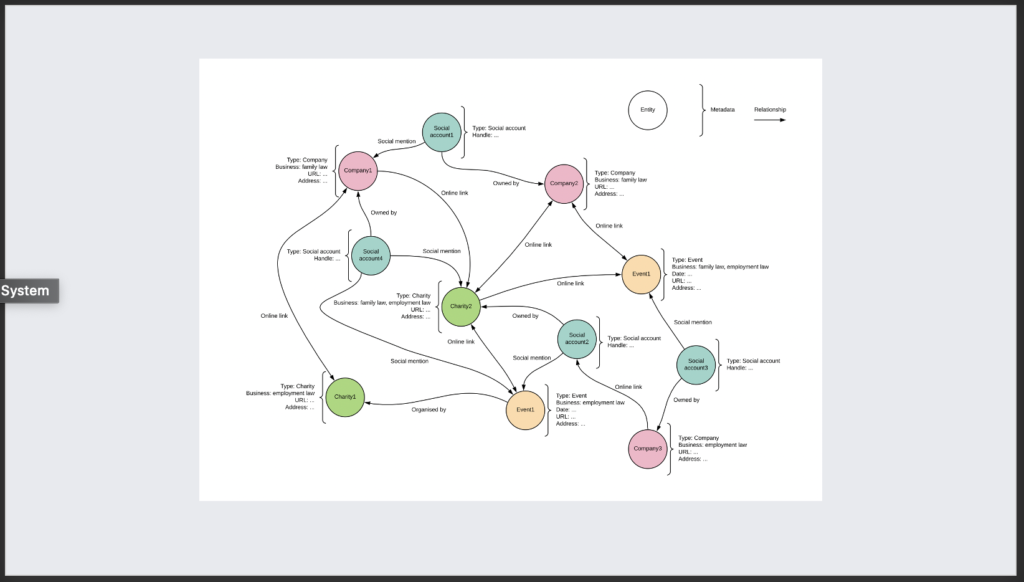

This is the ontology as we were building it – on our office wall!

An ontology is a model or diagrammatic representation of a particular domain (in this case, the access to justice system) which aims to identify and categorize all of the entities which exist within it as well as to map the various relationships between them.

Modelling the actors in the system and different kinds of relationships between them, and the direction of flows between them – eg. Flow and direction of money, decision-making; as it is and what it could afford, from the evidence. It is a way of representing how we understand the problem, as a whole team – incorporating our own different observations and perspectives based on evidence we had gathered.

This was how we started the process of analysing our desk research and fieldwork,

with the aims of:

• Identifying and classifying the various bodies who work within the sector – distinguished into classes such as Service Provider, Funder, Governing Body, Network, User, State

• Understanding the organisational structures and behaviours of these bodies – which we mapped as their attributes, which defines the class they are part of

• Mapping the relationships between these different bodies, based on eg. location, issues they deal with, clients, shared trustees or governance

• Tracing the flows of information, funding and decision-making power which drive the sector – which direction they flow in, between which actors; and what the system affords from the evidence but not currently how it’s structured to work

• Assessing the current level of digitalisation throughout the system and its various bodies

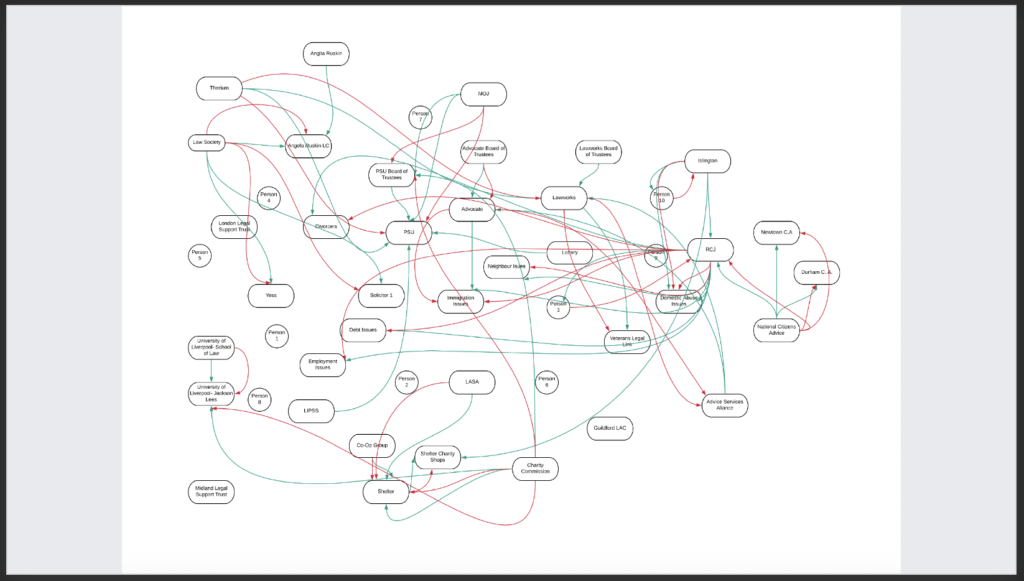

This slide shows our ontology mapping the flow of money through a subset of the system.

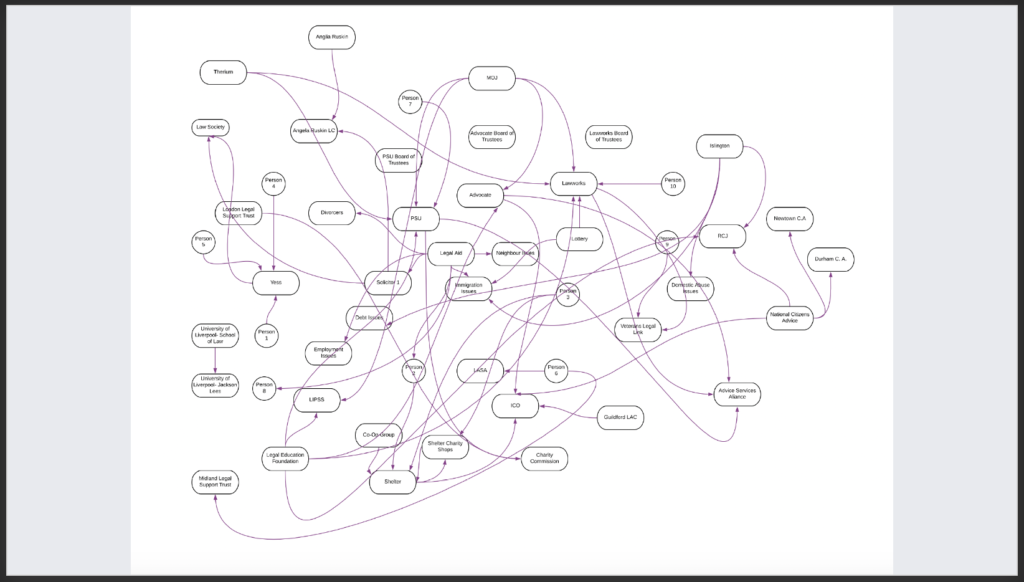

And this one shows our ontology mapping the flow of decision making through a subset of the system.

It is a method that:

Allows for the mapping of relationships between different entities

Allows us to identify optimal sites for a potential technological intervention

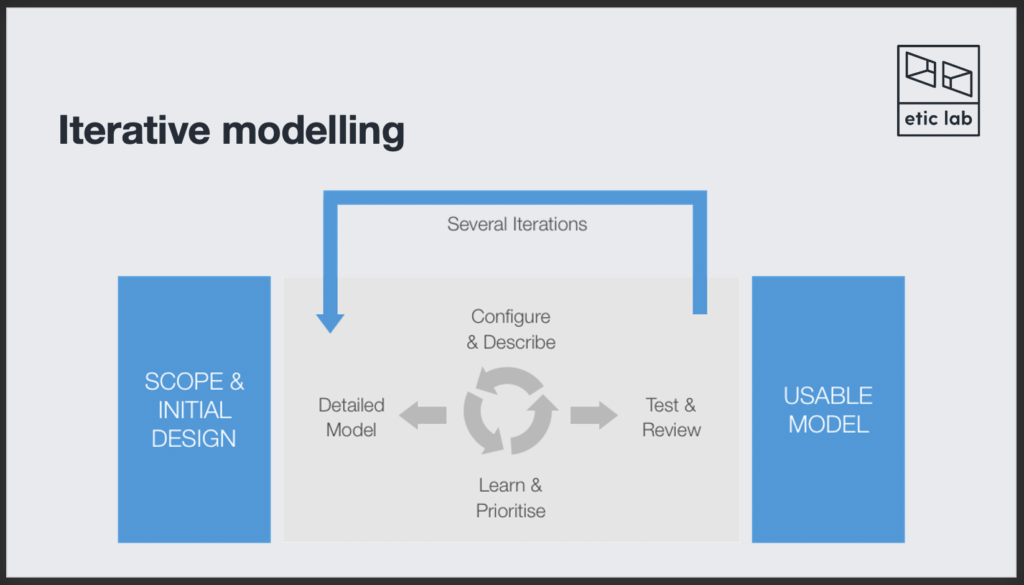

We described what we thought we had learned, analysed, discussed, modelled, argued about it, remodeled, tested; went through this process a number of times, mapping our findings about our view how the system works and what it affords;

using these models to question and refine our understanding of the system, allowing us in turn to construct richer and more consensual models.

We used the ontology to build a working model of the sector, to assess which technological interventions will have the most impact, and where they would need to be implemented for optimal effect.

EM: We’ll now try to describe each candidate in a little more detail, explain why each were chosen as a candidate any testing we did and why we recommend not taking it forward.

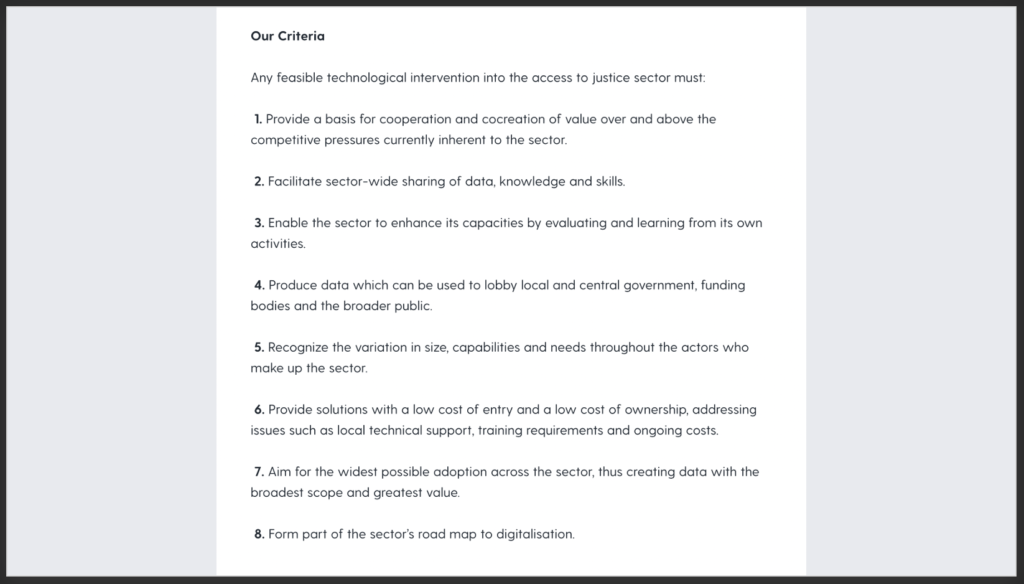

It is highlighted in the report and is pertinent to repeat it now – any successful technological intervention into the sector must be supported by sector-wide collaboration, co-production and the sharing of resources, expertise and data.

Breaking that down, the approach we’ve taken is to identify candidates with systemic impact. So, whilst an application which uses AI to automatically build legal documents would clearly provide great benefit to the sector, it would do nothing to tackle the broader challenges facing the sector today.

Our criteria for such a candidate has 8 parts (see slide)

Development costs – low cost solutions relatively speaking – scaleable but they’re not cheap.

Paradox: in order for these solutions to be cost-effective has to be adopted at scale. Tom can speak about this… he’s been crunching the numbers on the comms suite.

The first – which is the design and adoption of a common CRM for the sector which has the ability to facilitate data sharing, signposting and strategic coordination – is a ‘no-brainer’.

Big data (the collection and analysis of large datasets for underlying patterns and trends) and machine learning require immense volumes of cleaned, structured and standardised date in order to function.

One of our first questions therefore, was how to create a large enough pool of this relevant data…

The key takeaways:

- It would require a significant investment in time and money but would otherwise present few major technical barriers

- Securing buying from everyone is essential

- It would require consistent and proper usage

We quickly moved away from this candidate in favour of other candidates which provided the same benefit, without the legal, organisational and cultural barriers… I’ll now pass over to my colleague steph who will take us through the other candidates proposed.

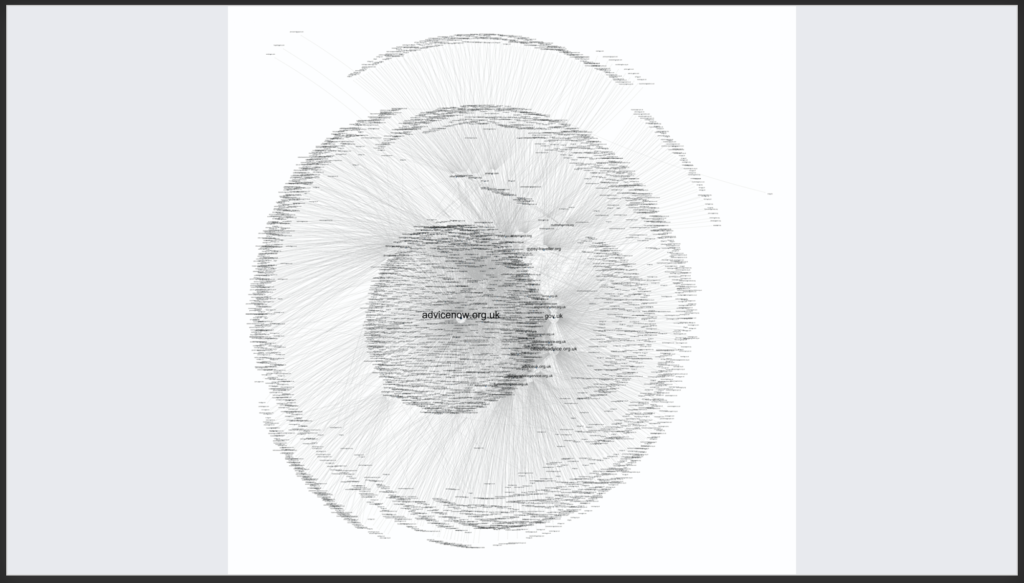

Building a digital Map, with the capacity to identify actors within the system, to pull out information such as addresses and opening times and to auto-update this information including updates to organisational turnover, using their digital traces, was one of our first thoughts.

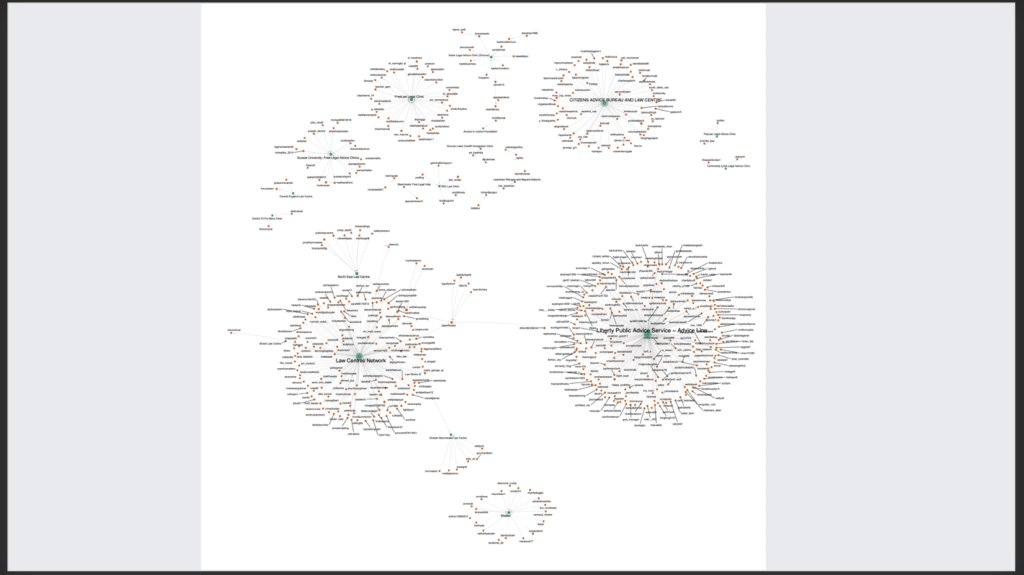

We developed an application we call the Etic Lab Network Analysis Tool, or ELNAT.

It is in fact a suite of tools capable of identifying actors within the sector from their digital presence, then evaluating their operations on the basis of several metrics, including level of digital maturity, web activity and content analysis, allowing for the real-time activities of the sector to be mapped and studied as the basis for future strategic initiatives. ELNAT is the software that has produced these network graphs:

Its functions comprise:

• Search – performs keyword searches of online databases, search engines

and social media to identify the web pages and social media accounts of organisations

seeking to engage with the access to justice sector

• Capture – ELNAT takes a snapshot of their online presence, producing a record of

what information and functionalities are available

• Classify – ELNAT uses this information to classify organisations based on location,

type and scale of services offered, level of digital maturity and several other

parameters

• Learn – All the data ELNAT collects is used to refine and focus its future searches,

making it faster and more accurate – a process generally known as machine learning

We have built a prototype version of this, which has supported our research, and enabled us to get an overview of the national picture, and to be able to zoom in to areas. We have used it to answer research questions in writing the report, and there has been a lot of interest in it, and its capacities for understanding the sector.

But in the end, we did not take it forward. initial development has already been paid for by Etic and Innovate, and although it has garnered much interest from the sector, and there is an obvious value it would have for the sector, there has been no collective will either to pool resources and collaborate on development around specific questions; or to fundraise to jointly pay for the rest of the development required, to the level of a universal tool with a user interface, and the associated cost of the storage of vast quantities of data to enable its ongoing running, for what would be a relatively cheap, certainly scalable and sustainable solution.

There is a relatively large initial cost of development work (large in terms of this sector’s resources) for each of these techs, but the value of their long-term scalability and sustainability, the low ongoing costs and benefits to the sector. Each of these technologies would also benefit the legal sector as a whole, giving insights and understanding that would aid decision-making and strategic planning.

It is in fact not a sector-specific tool.

This could be the most valuable tool we could build at the moment for overviewing entire sectors changes, and rates of changes, in real time both during and post-covid; for capturing and analysing the current very rapid changes caused by Covid-19 and the corresponding uncertainty; for capturing and keeping that information, in vast quantities, for future deeper research and analysis, learning.

Using the results of our desk research, ontology model and network directory tool, we have been building a mathematical model of the sector.

The model needed to be built for our research, as accurate data on the sector is almost non-existent. While ELNAT creates datasets, the mathematical model creates a picture of the sector from an analysis of the sector’s expectations – that is, it is a functional system model that approximates expectations of how the system should work, and can be used to test scenarios. It has been validated by real data. We have tested it using real historical data and the model stood up to this.

The model can be, and has been, used to:

- Trial different scenarios, and

- Test predictions across what actually happens

For example, the effect of doubling or halving funding, or aggregating a number of organisations. If you roll our model forward to predict near future scenarios, if it’s wrong – we will know.

We have not taken this forward for this sector for similar reasons to the Network Directory – we do not have a client prepared to pay for it. This is similarly an even more valuable tool in the current uncertain situation – the ability to model different possible scenarios, based on information gathered and automatically updated by our network directory would be unbelievably powerful for modelling different strategies for the future of any sector.

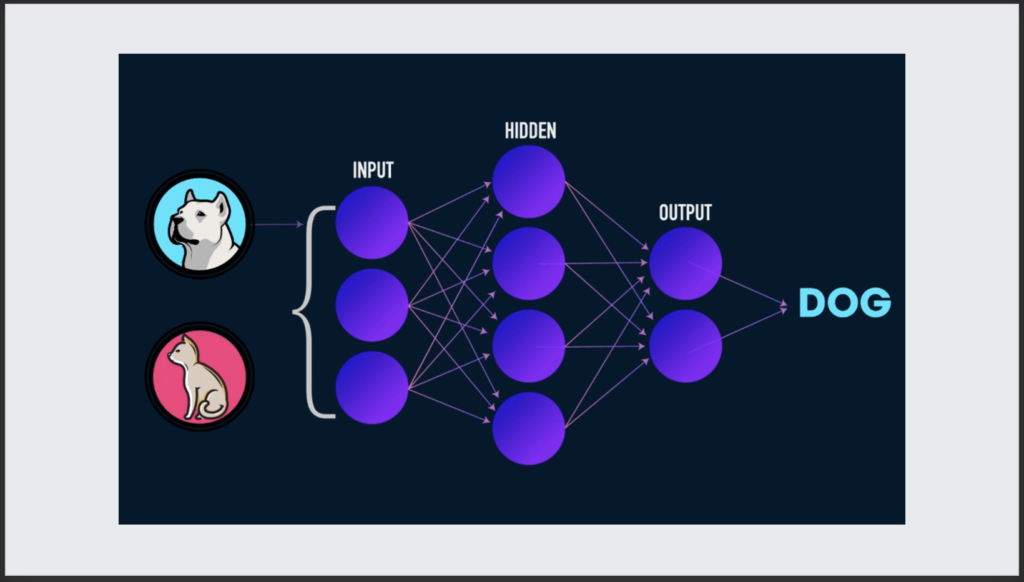

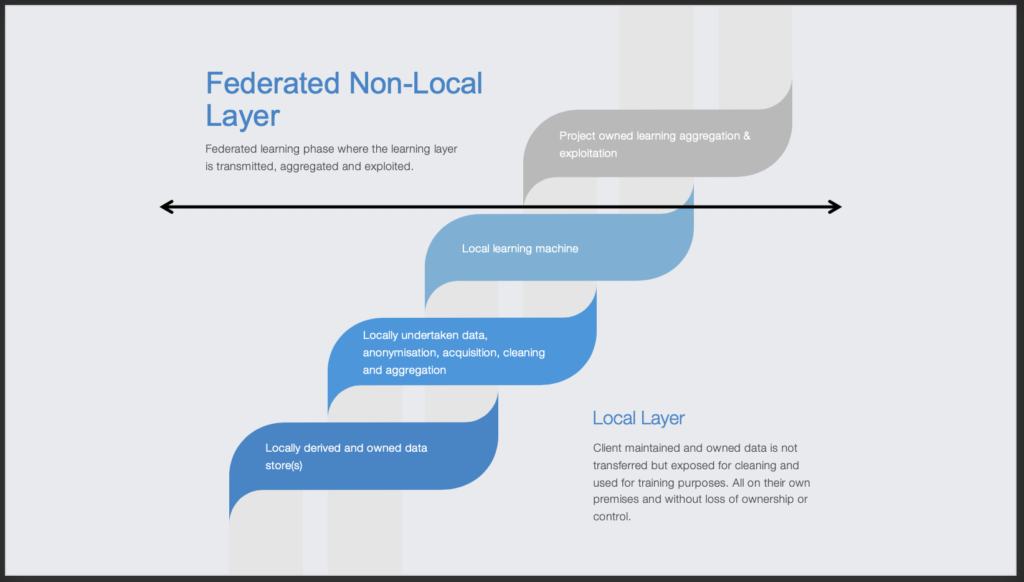

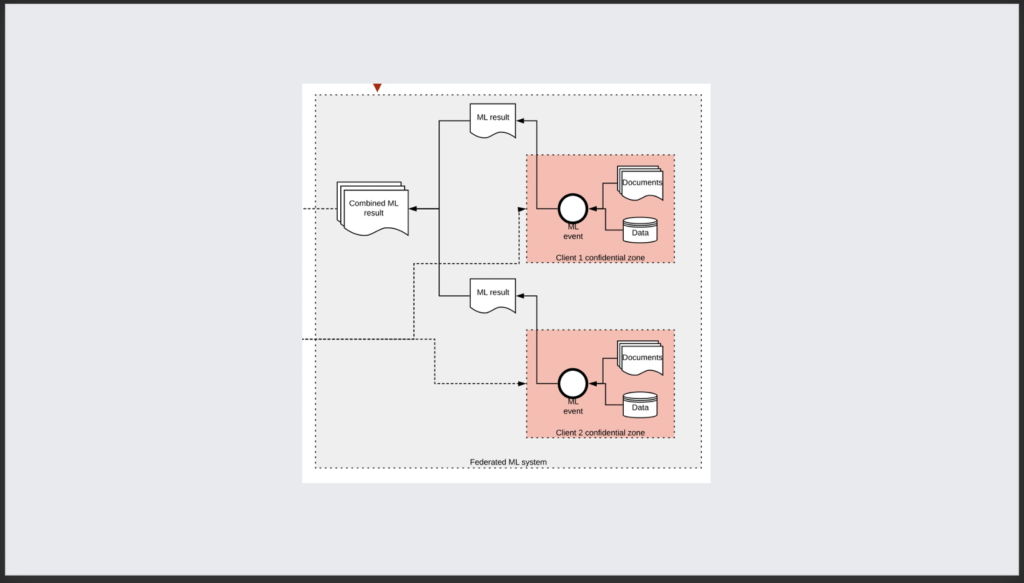

Federated Learning is a new technique which allows organisations to access the benefits of machine learning, such as the capacity for system-wide data analytics. ML analyses very large quantities of data through specific questions, for example making classifications based on a set of targets – very basically, like this example of image recognition (although actually this is a very hard task for machines).

and much more complex, to us, but simpler for machines, this network diagram clustering different types of entity in the access to justice system. This is the kind of task ML excels at, something that would take many many hours in manual computing, that once the specific ML algorithm is developed is extremely fast and continues to learn, exponentially refining accuracy as it gathers more data, tests its results on new data and iteratively learns from those processes.

ML requires access to the kind of very large quantities of data that none of the organisations in the sector hold, and would previously have required cross-organisational data sharing to benefit from it.

FL is a technique that allows the ML to be done at local sources, and only the results of that learning are shared.

It is a distributed machine learning approach which enables training on a large corpus of decentralised data residing on multiple different drives or servers (such as, for instance, the computer systems of a range of different legal advice providers). It allows the data from each of these different sources to be analysed independently, and then for the results of these analyses to be consolidated, providing the basis for training an algorithm as per conventional machine learning.

It bypasses many of the privacy- and data security-related risks and competition that currently prevent cross-organisational collaboration like this, and has the potential for enabling the sector to overcome its current state of technological and strategic fragmentation:

- Developing an infrastructure for strategic cooperation across the sector

- Enhancing the capacity of the sector as a whole to analyse and learn from its own activities

The successful implementation of technology depends upon the ability of the sector to organise itself into a democratic and inclusive community of shared interest. The virtue of a technology like FL, as with all of the candidate technologies we have discussed, is that once it is in place it will make the maintenance and extension of such a community that much easier, as the cooperative values which underpin it will have been baked into the technological systems that the sector is now using to organise its activities.

This is a project we are currently working on.

We have the prototype software built, and we have been working on federation-building with the Law Centres Network, who we would like to thank for their invaluable contribution so far. The core of federated learning lies in building the federation – like all of our candidates, it’s a process, not just a piece of software. It is all about facilitating meaningful collaboration without compromising data privacy, competition, or security. This involves working out ways of working together, establishing frameworks, protocols, common understandings and definitions; and which questions to ask, what we want to learn from the data.

For example, a burning question at the moment in light of Covid-19 is what are the current trends in legal advice sought? Have they changed, are they continuing to change? What is the demand and spread, has this changed?

The aggregation of learning from across the country would enable comparisons and strategic overviews to support decision-making. FL has the potential to powerfully develop and facilitate cooperative and competitive working practices.

Federated Learning is an extremely new technology, with a correspondingly small base of academic literature and research. Our analysis of the existing evidence base and consultations with experts (including a trip to the Media Lab at MIT) have led us to conclude that it would indeed be feasible to apply a version of FL within the access to justice sector. The question of how to share knowledge and develop the capacity for learning across the sector is so fundamental, we believe, that the feasibility of most, if not all other systemic technological interventions depends upon it. In other words, the fulfilment of our fundamental goal of using digital technologies to enhance access to justice may well depend on the implementation of FL. We have therefore made the decision to dedicate the remainder of our time and funding on the R2J project to developing an in-depth appraisal and working prototype of such a system.

We’ve saved the integrated comms suite for last given that we have been successful in obtaining emergency covid-19 funding for this project. This was not one of the report’s final two preferred candidates, but has become an urgent priority in relation to the pandemic. We have received funding to design and develop a dedicated communications suite for the access to justice sector, comprising videoconferencing, secure document transfer and a searchable list of authorised providers, on a short turnaround time of 26 weeks.

We’re looking for organisations to work on development with us, to trial it and for early access

EL Partner Tom is managing this project and will give some more detail before we end with final questions.